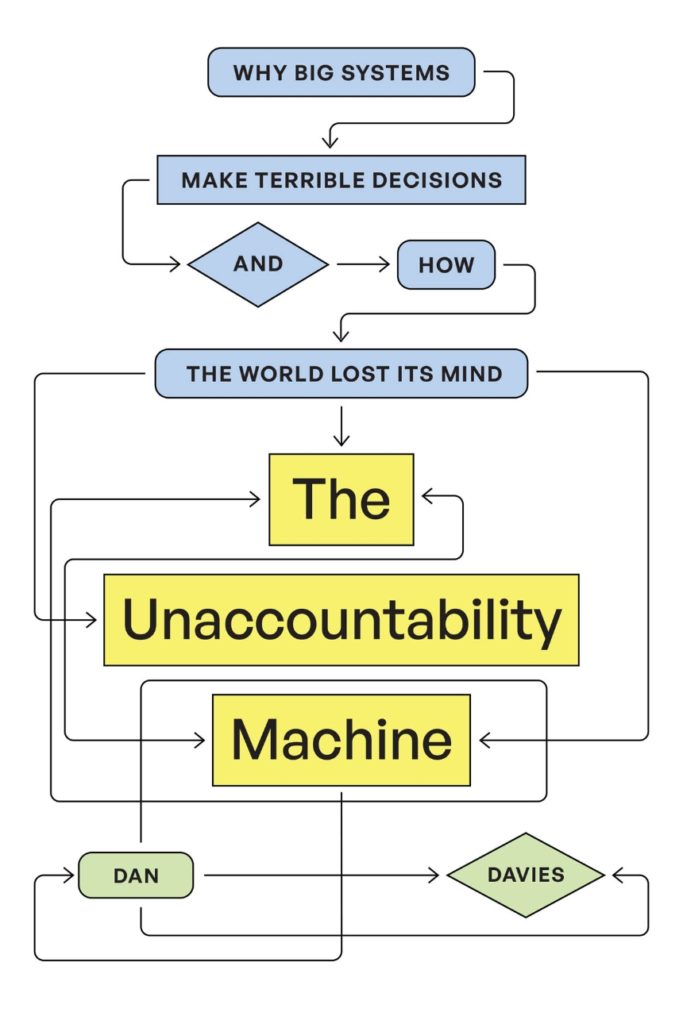

Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions—and How the World Lost Its Mind

Book authored by Dan Davies

I really loved this book. The works of Stafford Beer have been recommended to me directly by Peter Joseph and Jacque Fresco, but I’m someone who listens to audiobook and the original books both aren’t in an audiobook version (that I know of) nor are they particularly accessible. Dan Davies has explained how our current systems have created accountability sinks. Processes and decision making frameworks where it’s hard to specifically pinpoint a particular individual being the cause but instead the system itself not handling the variety of inputs and scenarios.

Examples include The Boeing 737 MAX Crisis, The COVID-19 Response issues by governments, Social Media and Democracy and especially content moderation issues. Even how hundreds of squirrels were shredded at an airport, or how there’s a Rise of Populism, from Trump in USA to Brexit in the UK, Modi in India, Bolsonaro in Brazil and more.

Best of all he does a great job summarising the Viable Systems Model, AKA Cybernetics and how understanding and applying it can help us fix the issues.

A big highlight for me was that there’s 5 different systems within an organisation and they all work on different aspects, but need both communication and translation layers between them. I’ve seen this with my own startup Drivible, because I’ll sometimes be in developer mode (usually doing PHP Programming) and be outputting lots of dense nerdy jargon and information. Then I’ll try to summarise some of it in the same Linear task for my co-founder, which is me switching to a manager and higher systems mode and doing that translation.

This book was only relatively recently released and references recent events. In fact the summary below was generated not just by Claude, but also using Open AI’s Whisper Speech to Text model.

That’s because the eBook is currently not available for this book, it’s only available as an audiobook, at least according to the Chicago University Press the eBook will be released in April 2025.

As such I converted my audiobook into MP3 and then used the Huggingface automatic-speech-recognition pipeline with openai’s whisper-large-v3 (English medium) model to convert the speech to text. I used the code examples and my very rudimentary Python to run it locally on my machine. I left it running overnight.

I then asked Claude to summarise the 454Kb worth of text.

Yes, that seems like a lot of work, but it saved me having to manually write up a detailed summary myself and this is a nearly 30min read and 5k words already.

Dan Davies also explains that private equity is a nasty issue in our current neo-capitalist system. By allowing a company to be purchased by someone else, with the company’s own debt, makes it hard to optimise for longer term things, or basically anything beyond short term profits.

As readers might know, I’m also running the Abundant Mars Podcast and I’m interested in knowing how to apply Cybernetics to how we’d run a base on Mars.

I have no affiliation with the author or publisher, I’m simply a reader who’s become a fan of the book and the ideas within and want a place I can send people to give them enough to be able to understand and hopefully they’ll buy it and actually read it.

Book links:

Chicago University Press https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/U/bo252799883.html

Profile Books https://profilebooks.com/work/the-unaccountability-machine/

Good Reads https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/197716282-the-unaccountability-machine

Amazon https://www.amazon.com/Unaccountability-Machine-Dan-Davies/dp/1788169549

Audible https://www.audible.com/pd/The-Unaccountability-Machine-Audiobook/B0CRJ9KY1G (where I got this from)

Summary

The key ideas of “The Unaccountability Machine” by Dan Davies. This book explores how modern systems and organizations have developed in ways that make it increasingly difficult to identify who is responsible when things go wrong.

The central concept Davies introduces is the “accountability sink” – systems where decisions are delegated to complex rulebooks or procedures, making it impossible to trace the source of mistakes. When something goes wrong, there’s often no clear person or entity that can be held responsible.

The book traces this phenomenon through several key developments:

- The rise of cybernetics and management theory, particularly through the work of Stafford Beer in the 1960s-70s. Beer developed an approach called the “viable system model” that aimed to create organizations that could adapt and remain stable while maintaining clear lines of accountability. His biggest test case was in Chile under Salvador Allende, but this experiment ended with the 1973 coup.

- The influence of economist Milton Friedman, whose 1970 doctrine that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits” helped reshape corporate governance. This led to an emphasis on shareholder value above all else, creating systems where managers could avoid personal responsibility by claiming they were just maximizing profits.

- The leveraged buyout boom of the 1980s, where financial engineering created complex corporate structures that further obscured accountability. Companies became loaded with debt, forcing them to prioritize short-term profits over long-term stability or social responsibility.

Davies argues that these changes have created a fundamental problem: our institutions are increasingly complex systems that no one fully understands or controls, yet they make decisions that profoundly affect people’s lives. This has contributed to rising public frustration and populist movements, as people feel powerless against unaccountable institutions.

A key insight is that this isn’t just about bad people avoiding responsibility – it’s built into how modern organizations work. The systems have become so complex that even those nominally in charge often don’t understand how decisions are really made.

Davies draws on cybernetics theory to explain why this happens. Systems need ways to process and filter information to function, but our current approaches often filter out important feedback and responsibility. This creates organizations that are technically efficient but increasingly disconnected from human needs and values.

The book suggests we need to rethink how we structure organizations to restore meaningful accountability while handling complexity. This might involve new ways of incorporating feedback from those affected by decisions and creating better channels for human judgment to override automated systems when needed.

The title “The Unaccountability Machine” refers to how our economic and political systems have evolved to systematically avoid accountability, almost like a machine that’s been programmed to deflect responsibility. The subtitle “Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions—and How the World Lost Its Mind” captures both the practical consequences (poor decisions) and the psychological impact (a feeling that the world has become irrational).

Highlights

Thanks to Amazon (wait, does that mean kindle readers have the ability to read this already?)

- Knowing a great deal of detail about a subset of a system has a habit of increasing your confidence in your opinions disproportionately from their reliability.

- They have constructed an accountability sink to absorb unwanted negative emotion.

- It is not necessary to enter the black box to understand the nature of the function it performs.

The 5 Systems, explained

Explaining cybernetics theory, particularly focusing on Stafford Beer’s “Viable System Model” (VSM) which describes how organizations can remain stable and effective while adapting to change.

The fundamental principle of cybernetics is about control and communication in complex systems. Think of it like conducting an orchestra – you need ways to coordinate many different parts while responding to changes and maintaining overall harmony.

Let’s walk through the five key systems in Beer’s model, which work together like the different parts of a brain:

System 1: Operations

This is the basic level that actually does things – like the musicians in our orchestra. These are the parts that interact directly with the environment, producing outputs and responding to inputs. In a company, these might be the manufacturing plants or service delivery teams.

System 2: Coordination

This system prevents conflicts between different operational units – like the sheet music and conductor’s baton keeping everyone in time. It creates stability by establishing standard procedures and protocols. In a business, this might include scheduling systems or resource allocation procedures.

System 3: Integration and Control

This is immediate management of the operations – like the conductor interpreting the music and directing the orchestra. It optimizes how different operational units work together and maintains internal stability. This level makes sure everyone is working toward common goals and using resources effectively.

System 4: Intelligence and Planning

This system looks to the future and the outside world – like someone studying musical trends and audience preferences to plan future concerts. It gathers information about the environment and potential changes, helping the organization to adapt and evolve. This might include market research or strategic planning departments.

System 5: Identity and Policy

This is the highest level, setting overall direction and balancing present needs with future development – like the artistic director deciding what kind of orchestra they want to be. It maintains the organization’s identity and core purpose while mediating between the day-to-day management of System 3 and the future-oriented planning of System 4.

A crucial concept in cybernetics is “requisite variety” – the idea that a control system must have at least as much complexity as the system it’s trying to control. Think of it like needing a steering wheel with enough range of motion to handle all possible turns a car might need to make.

Another important principle is the idea of “viable systems” being recursive – each operational unit (System 1) contains its own complete set of these five systems at a smaller scale. Like how each section of an orchestra (strings, brass, etc.) has its own internal coordination and leadership while being part of the larger whole.

The model emphasizes the importance of information flow between these levels. There need to be both:

- Regular channels for normal operation and reporting

- “Algedonic” (alert) signals that can bypass normal channels when something urgent needs attention

System 1 – Operations

Operations are the foundation of how organisations actually interact with their environment.

Think of System 1 as the collection of parts that actually “do” things in an organization. These are the units that carry out the primary activities that justify the organization’s existence. But what makes System 1 particularly interesting is that each operational unit is itself a complete viable system – meaning it could theoretically exist as an independent entity.

Let’s use a hospital as an example to understand this better:

In a hospital, System 1 operations might include:

- The emergency department

- The surgical unit

- The maternity ward

- The pharmacy

- The diagnostic imaging department

Each of these units can function somewhat independently and has its own internal management structure. The emergency department, for instance, has its own staff, procedures, and resources. It makes many day-to-day decisions without needing approval from higher hospital management.

What makes System 1 special is its direct contact with the environment. Each operational unit deals with real-world complexity that can’t be fully predicted or controlled. The emergency department faces a constant stream of unique cases, each requiring specific responses. This means System 1 units need significant autonomy to handle this variety of situations effectively.

However, this autonomy exists within what Stafford Beer called a “resource bargain.” Each System 1 unit negotiates with higher levels about what resources it needs (staff, equipment, budget) and what it promises to deliver in return (number of patients treated, quality metrics, etc.). This creates accountability while preserving necessary freedom of action.

A crucial aspect of System 1 is that it contains its own internal management systems. Using our emergency department example:

- It has its own coordination (duty rosters, triage procedures)

- Its own control (department head, charge nurses)

- Its own intelligence (tracking patient flow patterns, planning for major incidents)

- Its own identity (emergency medicine culture and values)

This recursive nature of viable systems is vital – it means each operational unit can handle most of its own problems without needing constant intervention from above. The higher levels of the organization only need to step in when issues affect multiple units or threaten overall stability.

The design of System 1 operations involves several key principles:

- Local Autonomy: Each unit must have enough freedom to handle its specific environmental challenges.

- Resource Adequacy: Units need sufficient resources to meet their commitments.

- Information Clarity: Clear channels must exist for both routine communication and emergency alerts.

- Accountability Balance: Units should be accountable for results while maintaining flexibility in how they achieve them.

Understanding System 1 helps explain why many modern organizational problems occur. When higher levels try to micromanage operational units or when resource bargains become too restrictive, the system loses its ability to handle real-world complexity effectively.

System 2 – Coordination

System 2 plays a crucial role in preventing chaos between different operational units, though it’s often underappreciated in organisations.

Think of System 2 as the traffic lights of an organization. Traffic lights don’t tell cars where to go, but they prevent accidents by coordinating movement. Similarly, System 2 creates stability by managing how different parts of the organization interact with each other.

Let’s use a university as an example to understand how System 2 works. In a university, System 2 coordination includes:

The Course Scheduling System: This prevents multiple classes from being scheduled in the same room at the same time. It’s not telling professors what to teach, but it’s ensuring they don’t conflict with each other. The system might seem simple, but it’s handling immense complexity – dealing with hundreds of courses, dozens of rooms, and various time slots.

The Resource Management System: When different departments need to share expensive equipment (like electron microscopes or computer labs), System 2 creates protocols for scheduling and usage. Without this coordination, you might have two research groups showing up to use the same equipment simultaneously.

The Academic Calendar: This coordinates activities across the entire university. It ensures exams don’t conflict with major campus events, that registration periods are synchronized, and that everyone is working on the same timeline.

What makes System 2 particularly interesting is how it operates. It doesn’t have direct authority over the operational units (that’s System 3’s job). Instead, it works through:

- Anti-oscillation Mechanisms: These prevent systems from working against each other. For example, if the physics department and chemistry department both try to schedule all their labs in the morning, System 2 prevents this conflict before it happens.

- Information Sharing: System 2 ensures different parts of the organization know what others are doing when it affects them. The library needs to know when midterms are happening to adjust their opening hours; the cafeteria needs to know about special events to plan their staffing.

- Standard Protocols: These are agreed-upon ways of doing things that prevent friction. Think of standardized forms for requesting resources, or common procedures for handling interdepartmental projects.

Stafford Beer emphasized that System 2 needs to be designed with care. If it’s too weak, you get chaos – departments working at cross purposes, resources being wasted, and constant conflicts. But if it’s too strong or rigid, it can stifle the necessary autonomy of operational units.

The key is to find the right balance. System 2 should be:

- Strong enough to prevent harmful interference between units

- Flexible enough to allow for necessary adaptation

- Efficient enough that coordination doesn’t become a burden

- Clear enough that everyone understands the protocols

In modern organizations, System 2 often manifests in:

- ERP – Enterprise resource planning systems

- Project management software

- Shared calendars and scheduling tools

- SOP – Standard operating procedures

- Communication protocols

When System 2 fails, you often see symptoms like:

- Double-booked resources

- Departments working at cross purposes

- Repeated conflicts over shared facilities

- Information getting lost between departments

- Unnecessary delays while units wait for each other

Understanding System 2 is crucial for diagnosing organizational problems. Often, what looks like a failure of management (System 3) or operations (System 1) is actually a coordination problem that could be solved with better System 2 mechanisms.

System 3 – Integration and Control

System 3 is one of the most crucial parts of any organization – it’s where day-to-day management happens and where the organization ensures its various parts are working together effectively.

Think of System 3 as the conductor of an orchestra. While System 2 provides the sheet music and basic coordination, System 3 actively interprets, directs, and manages the performance. It’s responsible for making sure all the parts create harmony rather than cacophony.

The main function of System 3 is to optimize how the organization works as a whole. It does this through what Stafford Beer called “resource bargaining” – negotiating agreements with operational units about what they’ll deliver and what resources they’ll get in return. Let’s explore how this works:

Resource Bargaining

Imagine a manufacturing company with three factories (System 1 units).

System 3 would:

- Negotiate production targets with each factory

- Allocate budgets and resources

- Set quality standards

- Monitor performance

- Adjust these agreements when circumstances change

The key insight is that these aren’t just top-down orders. They’re genuine negotiations where operational units can push back if demands are unrealistic or they need more resources. This two-way communication is essential for the system to work.

Management by Exception

Another crucial aspect of System 3 is that it operates by “management by exception.” This means it doesn’t try to control everything – it only intervenes when something falls outside agreed parameters. This preserves the autonomy of operational units while ensuring overall stability.

For example, if a factory is meeting its targets and staying within budget, System 3 leaves it alone. But if quality starts dropping or costs spike, System 3 steps in to investigate and help resolve the issue.

Three Channels of Control

System 3 operates through three main channels:

- The Command Channel: Direct management authority, like setting targets and allocating resources. This is the most visible but should be used sparingly.

- The Resource Bargaining Channel: Negotiating agreements about performance and resources. This is where most of the real work happens.

- The Audit Channel: Occasionally checking that what’s being reported matches reality. This maintains trust in the system.

Information Processing

System 3 has a crucial role in processing information. It needs to:

- Filter information from operations so higher levels aren’t overwhelmed

- Translate operational details into strategic insights

- Spot patterns across different units

- Identify potential synergies or conflicts

Common Problems

Understanding System 3 helps diagnose common organizational problems:

- Micromanagement occurs when System 3 tries to control too much detail instead of managing by exception

- Poor performance often results from unrealistic resource bargains

- Coordination failures happen when System 3 doesn’t help units work together effectively

- Information overload occurs when filtering mechanisms aren’t working properly

System 3 in Practice

In modern organizations, System 3 typically includes:

- Middle and senior management

- Financial control systems

- Performance management systems

- Quality control

- Resource allocation processes

The key to effective System 3 operation is balance. It needs to:

- Be strong enough to ensure cohesion

- Be light-touch enough to preserve autonomy

- Process enough information to spot problems

- Filter enough information to prevent overload

- Build trust while maintaining oversight

System 4 – Intelligence and Planning

System 4 is crucial for understanding how organizations adapt and survive in a changing world.

Think of System 4 as an organization’s eyes and ears focused on the future. While System 3 manages the present, System 4 scans the horizon, looking for opportunities and threats that might affect the organization. It’s like having a dedicated lookout on a ship, watching for both storms and favorable winds ahead.

The Core Functions of System 4

Future-Oriented Intelligence:

System 4 monitors the external environment and builds models of how it might change. In a company, this might involve tracking technological developments, changing consumer preferences, competitor actions, and regulatory changes. The key is that System 4 looks at things that aren’t immediately relevant to current operations but could become important.

For example, imagine a car manufacturer’s System 4 in 2010. While Systems 1-3 were focused on producing and selling current models, System 4 would have been studying electric vehicle technology, changing environmental regulations, and shifting consumer attitudes toward sustainability. This intelligence would later prove crucial for survival.

Strategic Planning:

Based on its understanding of possible futures, System 4 develops plans for adaptation. This isn’t just about making predictions – it’s about maintaining multiple possible scenarios and ensuring the organization can respond to whichever one emerges. The car manufacturer might develop plans for different scenarios: rapid EV adoption, hybrid dominance, or hydrogen fuel cells becoming viable.

Model Building:

A crucial but often overlooked function of System 4 is building and maintaining models of both the organization and its environment. These models help simulate different futures and test potential responses. The models need to be constantly updated as new information arrives.

Information Processing Challenges

System 4 faces some unique challenges in processing information:

- Signal vs. Noise: Not every change in the environment is significant. System 4 needs to distinguish between meaningful trends and random fluctuations.

- Time Horizons: Different threats and opportunities operate on different timescales. Climate change, technological disruption, and competitor actions all need different monitoring approaches.

- Uncertainty: The further into the future you look, the more uncertain things become. System 4 needs ways to handle this increasing uncertainty without becoming paralyzed.

Common Failure Modes

Organizations often struggle with System 4 for several reasons:

Underinvestment: Because System 4 doesn’t contribute directly to current operations, it’s often underfunded, especially during cost-cutting. This leaves organizations vulnerable to change.

Poor Integration: Sometimes System 4 becomes isolated from the rest of the organization, producing beautiful plans that never connect with operational reality.

Overwhelm: In our fast-changing world, System 4 can become overwhelmed by the sheer volume of potential changes to monitor.

Making System 4 Work

Effective System 4 operation requires:

- Dedicated Resources: People and systems focused on future planning, not distracted by current operations.

- Strong Connections: Regular communication channels with both System 3 (current operations) and System 5 (overall direction).

- Variety Management: Ways to filter and process environmental information without getting overwhelmed.

- Multiple Perspectives: Different viewpoints and approaches to avoid blind spots.

Modern Implementation

In contemporary organizations, System 4 often includes:

- R&D – Research and Development departments

- Strategic planning units

- Market research teams

- Competitive intelligence functions

- Innovation labs

- Corporate Venture Capital arms

A crucial point about System 4 is that it needs to maintain some independence from current operations while staying connected enough to influence them. This is why many organizations create separate innovation units or future-focused teams.

System 5 – Identity and Policy

System 5 represents the highest level of control in an organization and plays a crucial role in maintaining organizational coherence and purpose.

Think of System 5 as the consciousness of the organization. While System 3 manages the present and System 4 looks to the future, System 5 maintains the organization’s identity and makes fundamental decisions about what kind of entity it wants to be. It’s like the mind of a person – the part that maintains a consistent sense of self even as circumstances change.

The Core Functions of System 5

The primary role of System 5 is to balance different needs and perspectives within the organization. Imagine a university president who must balance competing demands: maintaining academic excellence, ensuring financial sustainability, preserving institutional traditions, and adapting to changing educational needs. System 5 provides the framework for making these trade-offs.

One of System 5’s most important functions is mediating between System 3 (present-focused management) and System 4 (future-oriented planning). These systems often pull in different directions. System 3 might want to maximize current efficiency, while System 4 sees the need for potentially disruptive changes.

System 5 decides how to balance these competing demands based on the organization’s core identity and values.

Consider a newspaper facing digital disruption.

System 3 might push to cut costs and maintain profitability in print operations.

System 4 might advocate for heavy investment in digital platforms. System 5’s role is to decide how to balance these based on the paper’s fundamental mission – is it primarily about journalism, or is it about making money? Different answers lead to different decisions.

Creating and Maintaining Identity

System 5 shapes organizational identity through several mechanisms:

Values and Culture

System 5 establishes and maintains the core values that guide decision-making throughout the organization. These aren’t just mission statements on walls – they’re active principles that influence how conflicts are resolved and resources allocated.

Purpose Definition

System 5 determines what Stafford Beer called “purpose in use” – not just what the organization claims to do, but what it actually does. This involves constant reflection on whether actions align with stated purposes.

Ethical Framework

System 5 sets the ethical boundaries within which the organization operates. These boundaries often go beyond legal requirements to reflect deeper organizational values.

Handling Complexity

System 5 faces unique challenges in managing organizational complexity:

First, it must handle “residual variety” – the complexity that lower systems couldn’t absorb.

When a problem is too big or fundamental for other systems to handle, it rises to System 5.

Think of a CEO deciding whether to merge with another company or completely change the business model.

Second, System 5 must maintain what Beer called “recursive coherence” – ensuring that decisions at different levels of the organization remain aligned with overall identity and purpose. This is particularly challenging in large organizations where many semi-autonomous units make their own decisions.

Common Failure Modes

Organizations often struggle when System 5 fails in specific ways:

Identity Crisis

When System 5 loses clarity about organizational purpose, the entire system can become directionless. This often happens during rapid change or after mergers.

Value-Action Gap

Sometimes System 5 espouses values that don’t match organizational behavior, creating cynicism and confusion throughout the system.

Overload

If lower systems aren’t filtering effectively, System 5 can become overwhelmed with operational decisions, losing its ability to maintain strategic focus.

Making System 5 Work

Effective System 5 operation requires:

Clear Values: Well-articulated principles that can guide decision-making throughout the organization.

Strong Filters: Mechanisms to ensure only truly fundamental issues reach System 5.

Reflection Time: Space for leadership to think deeply about identity and purpose rather than just reacting to crises.

Communication Channels: Ways to share identity and values throughout the organization while receiving feedback about how they’re being interpreted and applied.

In modern organizations, System 5 typically manifests in:

- Board of Directors

- Executive Leadership Teams

- Corporate Governance Structures

- Value Statements and Cultural Principles

- Strategic Decision-Making Processes

How all five systems work together to create a viable organisation

Using an orchestra as an extended metaphor of how the five systems of the Viable System Model work together.

Imagine a world-class orchestra. At its most basic level (System 1), you have the musicians actually playing their instruments. Each section – strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion – is itself a complete viable system with its own internal management and coordination. They’re the ones directly creating the music.

To keep these sections from interfering with each other, System 2 provides coordination mechanisms. Think of the sheet music, the conductor’s baton movements, and the established protocols for rehearsals and performances. These prevent chaos – ensuring everyone’s playing in the same key and tempo, and that rehearsal spaces are properly scheduled.

The conductor represents System 3, actively managing the current performance or rehearsal. They’re not just keeping time – they’re making real-time decisions about interpretation, balance, and dynamics. They’re ensuring that all the sections work together to create a cohesive whole. The conductor negotiates with each section about their role and needs (resource bargaining) and intervenes when something isn’t working (management by exception).

Meanwhile, the artistic director or programming committee serves as System 4, thinking about the orchestra’s future. They’re studying musical trends, audience preferences, and potential repertoire. They might be considering whether to expand into film scores, how to incorporate digital elements, or whether to commission new works. They’re looking for both opportunities and threats on the horizon.

System 5, perhaps embodied in the board of trustees and senior leadership, maintains the orchestra’s fundamental identity. Are they primarily a traditional classical orchestra, or do they want to be known for contemporary music? Should they prioritize recording or live performance? How do they balance artistic excellence with financial sustainability? These basic questions shape all other decisions.

Now, let’s see how these systems interact in practice:

When something goes wrong during a performance (say, a musician falls ill), the response shows the systems working together:

- System 1 (the affected section) recognizes the problem

- System 2 ensures other sections are informed if needed

- System 3 (the conductor) makes immediate adjustments

- System 4 might consider if this suggests a need for backup players

- System 5 ensures any response aligns with organizational values

The key to viability is that these systems maintain appropriate relationships with each other:

Between Systems 3 and 4

There’s a constant dialogue between present needs and future possibilities. The conductor (System 3) might want to perfect the current repertoire, while the artistic director (System 4) sees the need to develop new capabilities. System 5 helps balance these competing demands.

Between Systems 1 and 3

The resource bargaining process is crucial. Each section needs enough autonomy to handle its specific challenges while remaining accountable for contributing to the whole. The conductor provides direction without micromanaging.

Between Systems 2 and 3

Coordination mechanisms need to be strong enough to prevent chaos but flexible enough to allow adaptation. The conductor can override standard procedures when artistic needs demand it.

All these relationships are supported by two types of communication channels:

Regular Channels:

- Regular reporting and feedback

- Standard procedures and protocols

- Routine meetings and reviews

Algedonic (Alert) Channels:

- Emergency signals that can bypass normal channels

- Direct communication paths for urgent issues

- Feedback mechanisms for serious problems

The strength of this model is that it creates stability while allowing for adaptation. Each system has its role, but they work together to maintain viability:

- System 1 provides the basic capability to function

- System 2 prevents destructive interactions

- System 3 optimizes current operations

- System 4 prepares for the future

- System 5 maintains identity and coherence

You can learn more by reading to the book or listening to the audiobook.

Book Title: The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions – and How The World Lost its Mind

Author: Dan Davies

I you read that and still want more than Dan Davies has also suggested some other books / primary sources.

First, Davies offers two important caveats about cybernetics literature:

- These books can be expensive, as many were published by academic presses. He suggests looking for second-hand copies, noting that retiring management consultants often donate their collections to charity shops and used bookstores.

- Many of these works contain complex mathematics. However, he reassures readers that they can usually skip over the equations while still understanding the core concepts.

For those starting their journey into cybernetics, Davies recommends beginning with:

“An Introduction to Cybernetics” by W. Ross Ashby (Chapman and Hall, 1976)

Davies considers this the best starting point as it was written as a basic text for biomedical researchers and only requires high school mathematics.

For those interested in the history and characters of cybernetics, he highly recommends:

“The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future” by Andrew Pickering (University of Chicago Press, 2011)

Davies particularly praises this book for capturing the eccentricity and genius of British cyberneticists, saying it’s worth paying full academic price if necessary.

“The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood” by James Gleick (Fourth Estate, 2012)

This tells the American side of the story, focusing on the telecoms engineers and computer programmers who attended the Macy conferences.

For Stafford Beer’s core works, he identifies two essential texts:

“Brain of the Firm” by Stafford Beer (John Wiley, 1972/1981)

Davies recommends getting the 1981 second edition if possible, as it contains significant updates. He notes this is the more rigorous but challenging text.

“The Heart of Enterprise” by Stafford Beer (John Wiley, 1979)

This is described as more user-friendly while still being essential reading.

For those wanting a more structured introduction to Beer’s ideas:

“Diagnosing the System for Organizations” by Stafford Beer (John Wiley, 1985)

This serves as Beer’s own textbook, replacing complex mathematics with diagrams.

For Beer’s broader social and economic thinking:

“Platform for Change” (John Wiley, 1975)

“Designing Freedom” (John Wiley, 1975)

There are also two collections of shorter pieces that Davies recommends as good entry points:

“How Many Grapes Went Into the Wine?” edited by Roger Harnden and Elena Leonard (John Wiley, 1994)

“Think Before You Think” edited by David Whittaker (Wavestone Press, 2009)

For understanding Beer himself, Davies recommends:

“Stafford Beer: The Father of Management Cybernetics” by Vanilla Beer and Elena Leonard (2019)

This includes a graphic novel biography and a useful glossary of cybernetic terms.

For the Chilean project specifically:

“Cybernetic Revolutionaries” by Eden Medina (MIT Press, 2011)

Davies calls this the definitive account of what happened in Chile.

For broader management and economic context:

“The Managerial Revolution” by James Burnham (John Day, 1941)

“The New Industrial State” by J.K. Galbraith (Horton Mifflin, 1967)

“Strategy and Structure” by Alfred D. Chandler (MIT Press, 1969)